Belemnite phylogeny

Belemnites are some of the most well-known fossils from the Mesozoic and are commonly used in geochemical studies due to their calcitic rostra that are relatively resistant to diagenetic overprint (Hoffmann & Stevens 2020). However, their evolutionary history is poorly understood, which has potential ramifications for the applicability of these methods due to undetected evolutionary constraints on rostrum geochemistry.

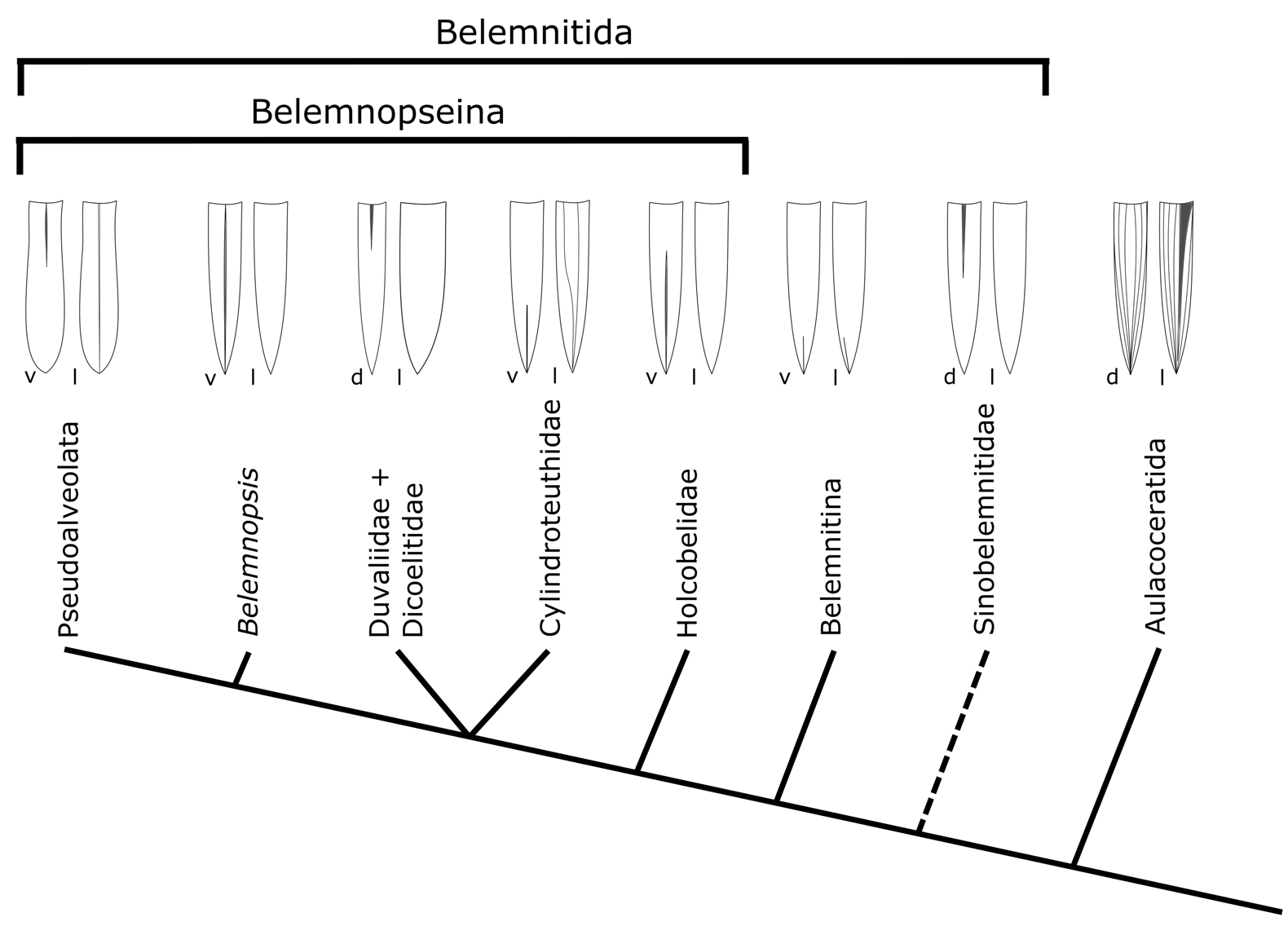

In this project, we attempt to reconstruct the phylogeny of belemnites using modern tools of Bayesian inference for the first time. A first study has been published in Palaeontologia Electronica, where we showed that previous classification concepts divided belemnites in groups that we have shown to be paraphyletic (Stevens et al. 2023). Instead, we suggested a revised phylogenetic classification of belemnites that shifts some of the formerly recognised families between Belemnitina and Belemnopseina, in addition to the recognition of a new unranked monophyletic group, the Pseudoalveolata (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Simplified belemnite phylogeny. From Stevens et al. (2023).

Fig. 1. Simplified belemnite phylogeny. From Stevens et al. (2023).

This study represented a first step, though the scarcity of characters means that there are still many uncertainties left. Ongoing work tests the applicability of further characters to belemnites (e.g., geochemistry), as well as investigating the phylogenetic position of belemnites within the cephalopod tree.

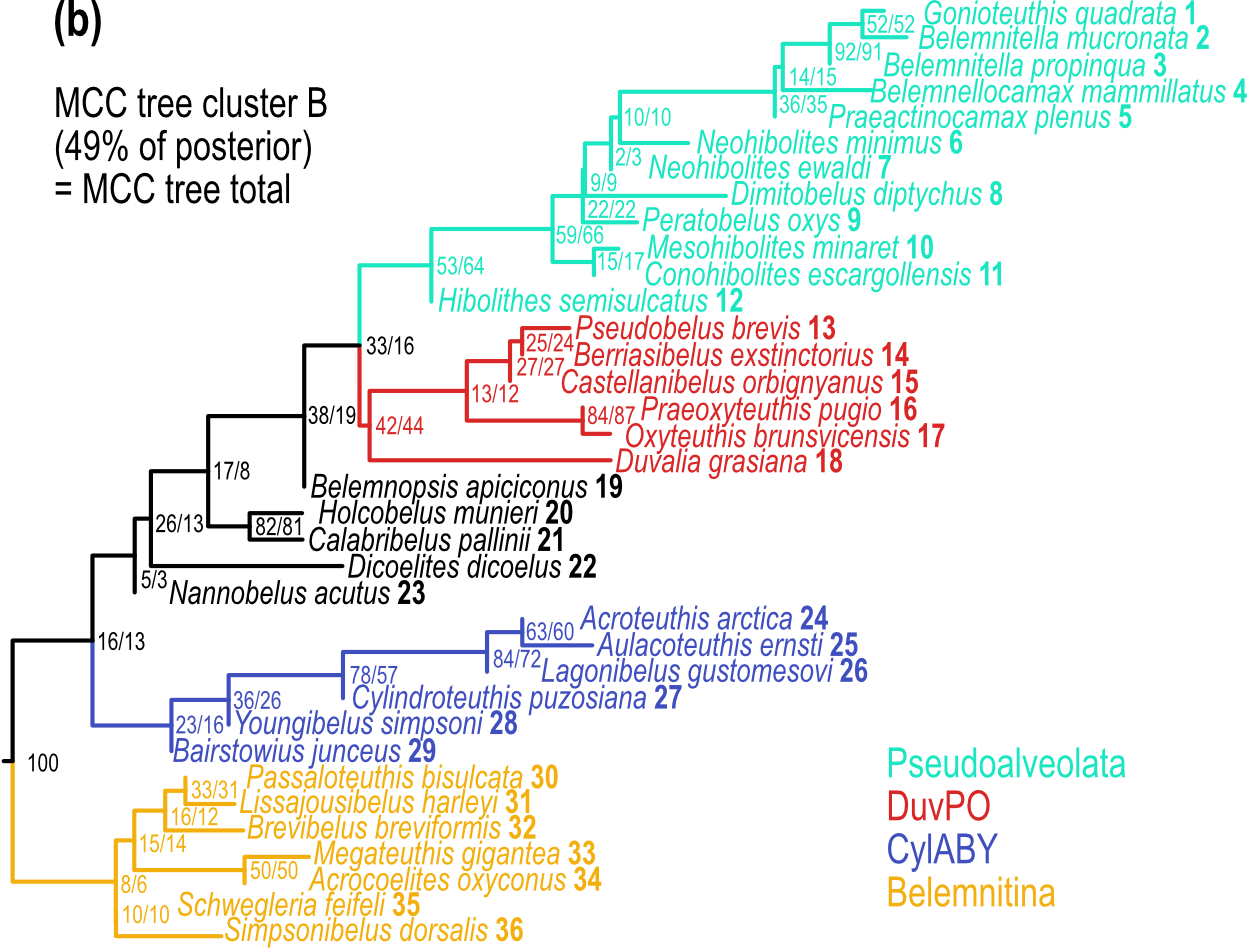

Another study aimed at investigating the potential of the chemical composition of the belemnite rostrum as a phylogenetic character (Pohle et al. 2025). For this purpose, we assembled a large literature database of Mg/Ca, Sr/Ca, Fe/Ca and Mn/Ca ratios in taxonomically identified belemnite rostra (Pohle et al. 2024). We then updated the phylogeny from Stevens et al. (2023) to include missing taxa for which geochemical data was available. The updated morphological character matrix was then used to infer a new phylogeny. Due to the high volatility of the clades, we investigated the resulting treespace using tools of principal coordinate analysis, which revealed that the treespace can be roughly divided into three clusters (a summary tree of the largest cluster is shwon in Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Details of the updated belemnite phylogeny. DuvPO refers to a clade containing the Duvaliidae, Praeoxyteuthis and Oxyteuthis, while CylABY contains the Cylindroteuthidae, as well as Aulacoteuthis, Bairstowius and Youngibelus. Numbers at nodes represent posterior probablities, with the first value only including trees from the same tree cluster, while the second value refers to all trees in the posterior sample. From Pohle et al. (2025).

Fig. 2. Details of the updated belemnite phylogeny. DuvPO refers to a clade containing the Duvaliidae, Praeoxyteuthis and Oxyteuthis, while CylABY contains the Cylindroteuthidae, as well as Aulacoteuthis, Bairstowius and Youngibelus. Numbers at nodes represent posterior probablities, with the first value only including trees from the same tree cluster, while the second value refers to all trees in the posterior sample. From Pohle et al. (2025).

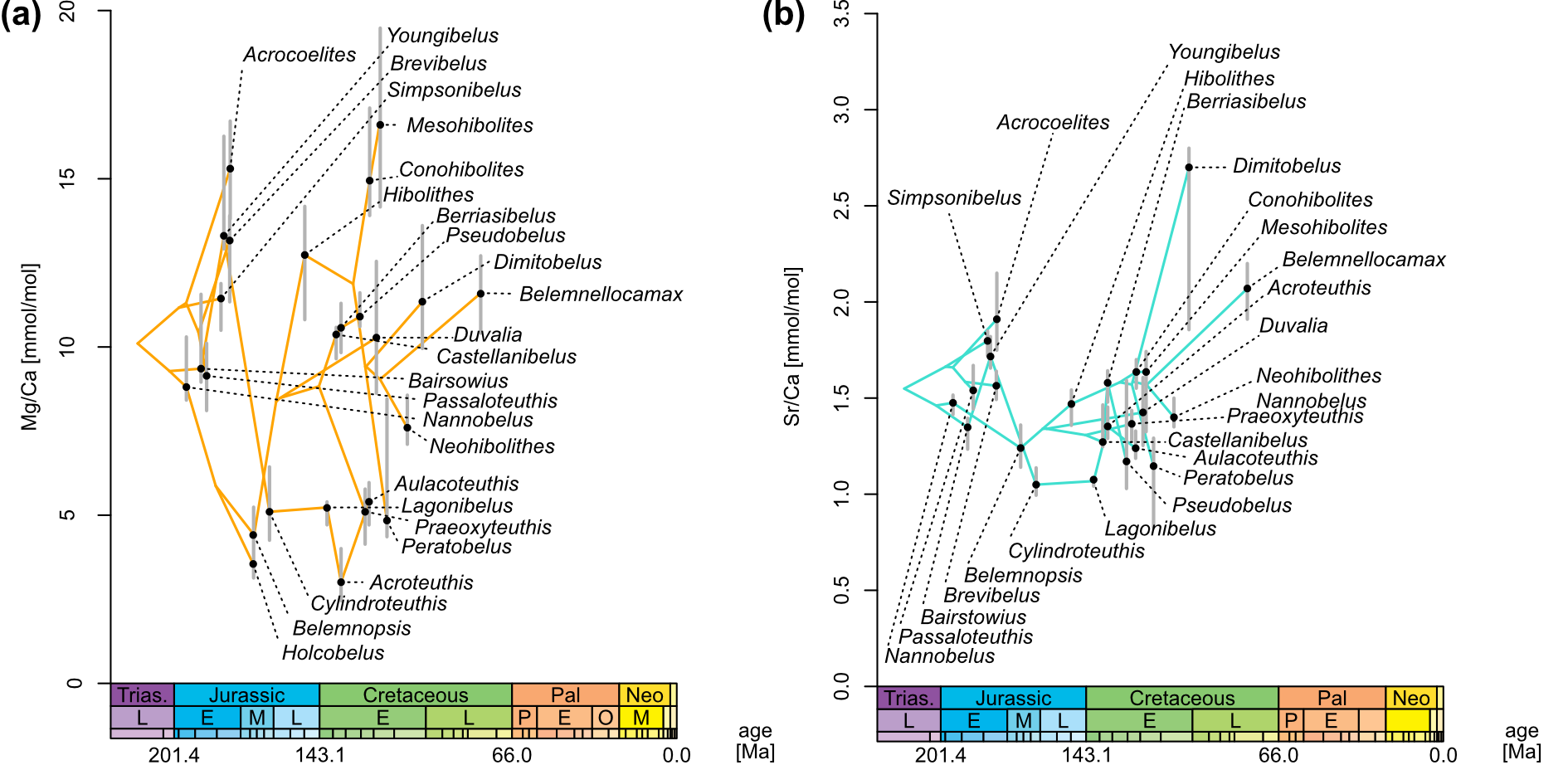

When changes in element ratios are reconstructed across the tree using tools of comparative phylogenetics, the changes do not appear to correlate closely with phylogeny (Fig. 3). This may mean that changes are more rapid than can be traced with our approach, which is also indicated by the rapid evolutionary rates inferred from a simple model of Brownian motion, which implied changes in both Mg/Ca and Sr/Ca ratios of about 12% of the respective mean values within 1 Myr. Another possibility is that element ratios are more strongly constrained by environmental factors and rapid changes imply frequent transitions into different environments. It is likely that there is not a single factor solely responsible for changes in element ratios, and that they reflect a complex interplay of taxon-specific, ontogenetic, kinetic, environmental and if material is not selected carefully also diagenetic effects.

Fig. 3. Phenogram of evolutionary changes in Mg/Ca (left) and Sr/Ca (right) ratios. From Pohle et al. (2025).

Fig. 3. Phenogram of evolutionary changes in Mg/Ca (left) and Sr/Ca (right) ratios. From Pohle et al. (2025).

Although our initial hopes of using geochemistry as an additional character for phylogenetic analyses were unfulfilled, the “phylogeochemistry” approach we established represents a promising opportunity for future studies, where ancestral state reconstruction of proxy data can be used to retrieve new information on environmental or climatic impacts on the evolutionary history of a clade. For example, a temperature proxy could be used to investigate the frequency of evolutionary warm-cold water transitions. Essentially, rather than comparing a phylogenetic tree to a single (global) temperature curve, local conditions of the populations are directly taken into account.

References

- Hoffmann, R. & Stevens, K. (2020). The palaeobiology of belemnites – foundation for the interpretation of rostrum geochemistry. Biological Reviews, 95(1), 94-123. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12557

- Pohle, A., Stevens, K., Hoffmann, R. & Immenhauser, A. (2024). Supplementary material: Phylogeochemistry: exploring evolutionary constraints on belemnite rostrum element composition [Data set]. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14004248

- Pohle, A., Stevens, K., Hoffmann, R. & Immenhauser, A. (2025). Phylogeochemistry: exploring evolutionary constraints on belemnite rostrum element composition. Biogeosciences, 22(12), 3073-3102. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-22-3073-2025

- Stevens, K.*, Pohle, A.*, Hoffmann, R. & Immenhauser, A. (2023). Bayesian inference reveals a complex evolutionary history of belemnites. Palaeontologia Electronica, 26(1), a13. https://doi.org/10.26879/1239

*Contributed equally